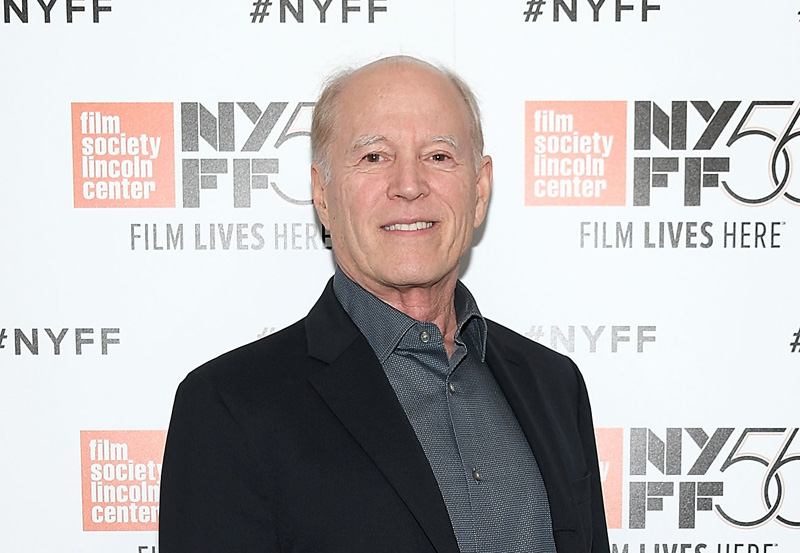

Netflix provided ComingSoon.net with the chance to sit down 1:1 with mega-producer Frank Marshall (Indiana Jones franchise, Jurassic franchise, Bourne franchise) for The Other Side of the Wind, the long-awaited final film from master director Orson Welles. Before he became Steven Spielberg’s go-to producer and a director in his own right (Arachnophobia, Congo), Marshall served as production manager of what became Welles’ final directorial effort when it first began shooting. Check out the interview below!

RELATED: Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind Trailer and Poster!

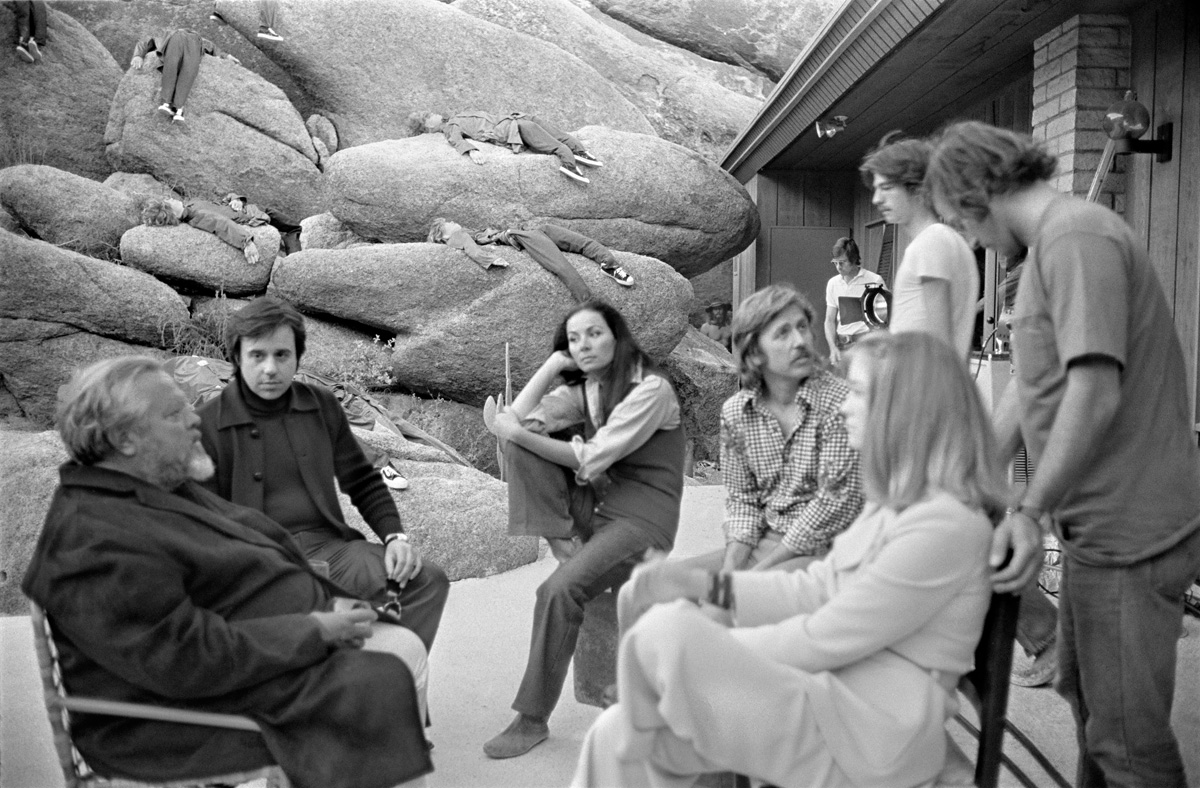

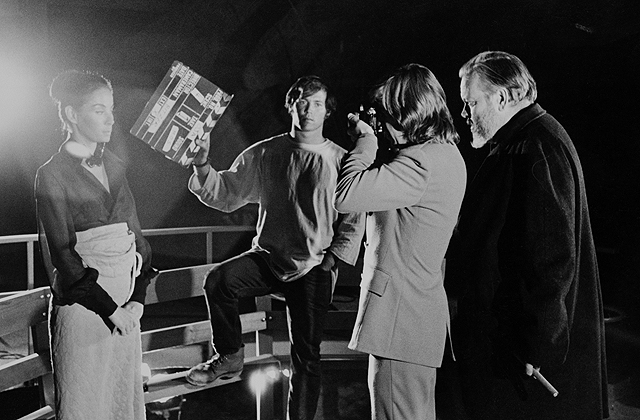

In 1970, legendary director Orson Welles (Citizen Kane) began filming what would ultimately be his final cinematic opus with a cast of Hollywood luminaries including John Huston, Peter Bogdanovich, Susan Strasberg and Welles’s partner during his later years, Oja Kodar. Beset by financial issues, the production ultimately stretched years and gained notoriety, never to be completed or released. More than a thousand reels of film negatives languished in a Paris vault until March of 2017, when producers Frank Marshall (who served as Welles’s production manager during his initial shooting) and Filip Jan Rymsza spearheaded efforts to have the film completed after over 40 years.

Featuring a new score by Oscar-winning composer Michel Legrand and reassembled by a technical team including Oscar-winning editor Bob Murawski, The Other Side of the Wind is Orson Welles’s vision fulfilled. It tells the story of grizzled director J.J. “Jake” Hannaford (Huston), who returns to Los Angeles after years in self-exile in Europe with plans to complete work on his own innovative comeback movie. Both a satire of the classic studio system and the New Hollywood that was shaking things up, Welles’s last artistic testament is a fascinating time capsule of a now-distant era in moviemaking as well as the long-awaited “new” work from an indisputable master.

RELATED: They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead Trailer Celebrates Orson Welles

The film was directed by Orson Welles, and produced by Frank Marshall (Indiana Jones series, Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom) and Filip Jan Rymsza (Valley of the Gods).

The Other Side of the Wind is now streaming on Netflix.

ComingSoon.net: This was a famously long, drawn out shoot. How did you initially get involved and what portion of the shoot were you a participant in?

Frank Marshall: I had done two movies with Peter and Polly Platt, and we had just finished “The Last Picture Show.” We had gone back to LA, and obviously Peter and Polly were with Orson. I just got a call one day, it was in ’71, from Polly saying, “I’m going to go down to Arizona. Orson asked me to come help him with this movie. Do you want to go?” And I said, “Are you kidding? What do you want me to do?” She said, “I don’t know. We’re just going…” I had bought a Volkswagen van in Archer City on “The Last Picture Show,” so I was free and mobile, threw my stuff in my van and I drove up to this house, and sure enough there was Orson Welles and about four other people and Polly. We stayed in this house for I don’t know how many weeks, but we were really shooting the movie within the movie. I didn’t see a script, and I know he was writing the script then. I seemed to have done a good job, pleased him. The DP Gary Graver obviously was there. He was really the overall production person pulling things together for Orson. Then we came back and we went away to make “What’s Up, Doc?” and Gary came back and they were shooting something in LA then. I would get this call from Gary to come back and work. It was always for free, but I didn’t care. So over those next couple of years I had a bunch of shoots in LA, and always asked my friends to come and work and be extras and things. Then I got this call from Orson where he said, “I got some money, and we need to hire all of the actors. And I’ve got the script.” That’s when the big carefree shoot happened with John Huston and Mercedes McCambridge and everybody else. I became sort of a line producer, production manager. I had done three or four movies by then. I pulled that together, and it was what I call an actual real shoot, where we had rooms and a caterer and crew and equipment and gasoline, because that was back in the gas days, where you hit the light and your car is up. There was only gas being pumped for a certain amount of time.

CS: Gas crisis.

Marshall: Gas crisis, yeah. It’s weird to think about it today. I worked on and off, and then finally in ’75 or ’76 I said, “I’ve got to make a living and a career.” He had finished pretty much the shooting then and was just trying to get a cut and be done with post. Then we lost him in ’85, and that’s when Gary really started trying to finish the movie. I got involved in trying to help Gary, and Peter got involved. We went around and around for a long time, until Netflix stepped up. I met Philip, who really… Without him we couldn’t have gotten all the rights.

CS: Orson had completed several scenes in an unorthodox, kaleidoscopic sort of editing style. How difficult was it for you and Bob, as the editor, not to impose on the template that Orson had already created?

Marshall: Those sequences that he cut, which were many, served as a guidepost for Bob on the style. We had several sequences that he had strung together, so we knew the setup that he wanted and what the next setup would be. He just hadn’t picked the takes. He’d have three takes of each setup. It was kind of an interesting way to edit, and they’re all on film, the work print. We would pick the take, and that was pretty easy, actually, but we knew what he wanted. The great thing was that we had edited sequences from different parts of the movie, so we had the film within the film. We knew what he wanted there. We had the scene at the studio in the screening room with the Bob Evans character. We had that. We had the beginning of the party scene. So we knew how crazy it was. He guided us in our decisions, is the way I like to look at it.

CS: What’s crazy is that staccato editing style, back in the day, might’ve been seen as weird or avant-garde. Now, in the post-MTV, post-Tony Scott, post-Michael Bay world, taking it in is as easy as breathing.

Marshall: Oh yeah, really ahead of his time in that.

CS: He was the original ADD filmmaker.

Marshall: Exactly. But I like to look at it in that he was just trying to push the envelope on film language and how to tell a story, which he would do with every movie. He didn’t make the same movie twice.

CS: From your perspective, how closely does the relationship between Peter and John in the movie mirror the relationship between Orson and Peter?

Marshall: I think that you can’t help but make comparisons there. It’s complicated. Friendships are complicated, and I think Orson might’ve been basing the character on Peter originally, but as you know, Peter was playing somebody else when we started. It was somebody who did imitations of a young successful director. I also think that Huston was based on Orson.

CS: But there’s also that aspect of John Huston also playing the Ernest Hemingway-esque director, which very much John and not Orson.

Marshall: A lot. Yes, exactly. I think you have to admit that a lot of what was going on there was the complicated relationship that Peter and Orson had.

CS: Orson went to great lengths to gather funds to make the movie and relied on volunteers and young people. I already know the story about how Welles edited the porno film for Gary, but do you have any other sort of crazy stories of how he pulled this film together?

Marshall: He was off doing whatever commercial he could do, whether it was Gallo Wine or something else. He would take anything. There are now infamous things I think on YouTube where he screams at the directors and everything. You know, he was a perfectionist, and he also was kind of… what would I call him? A court jester. You know, he loved to cause problems and he knew he was causing problems.

CS: The enfant terrible.

Marshall: That’s it. But on the other hand, he was just wonderful, had a great sense of humor, extraordinarily genius talent as an artist. We would go through these periods where we wouldn’t shoot and he’d go off and I’d hear he’s off doing a radio commercial or something. He’d get $10,000 and we’d be back in business. I can’t really think of anything other than that, but he was working to work. It’s kind of sad, because we really thought when he got the AFI Tribute and we went there and presented three scenes and Frank Sinatra was the master of ceremonies, and Orson gave a great speech about cinema and Hollywood and everything… nobody stepped up to help us. It’s kind of amazing. They were all incredibly scared of him, you know?

CS: I mean, you know this as well as anybody, there is a certain level of fear about hiring the artist who is going to chafe at being told what to do.

Marshall: Yeah, but you know, the movies are a balance. It’s always been this interesting balance between art and commerce. And hey, why not err on the side of art once? Make the movie you want. This is the guy who made “Citizen Kane” and “Ambersons” and “Touch of Evil.” He’s got a good movie in him. So but nobody would take the risk. This movie proves that it was worth it. Can you imagine seeing this movie in 1978?

CS: If it had come out right at the cusp of the new Hollywood, it would’ve been of its time. If it had come out in the 80’s, it might’ve been a little passé. In 2018, with media oversaturation and rise of meta narrative, it’s just right on the money now.

Marshall: Yeah, it’s amazing how relevant it is today.

CS: Was there anything that shocked you when you watched it, like, “geez, this is like right now?”

Marshall: Well, in the movie the guy is the sex object. That’s of today. “Oh look, how modern of Orson.”

CS: That’s so true. I didn’t think about that.

Marshall: You know? I am thrilled, I was thrilled that we had the whole movie. I didn’t really know until we got everything that we had shot, or he had shot most of the movie. I was really happy. You can imagine if we didn’t have Edmond O’Brien announcing each time the lights went out, or if we didn’t have the scene at the drive-in. I remember shooting in a drive-in because we got busted.

CS: You’re in that scene.

Marshall: Yeah, yeah, but I didn’t remember whether we had Peter talking to Norman Foster. I don’t remember any of that. We got busted at the drive-in. It was in the daytime and a police car came. And they said, “What are you doing here?” I said, “Well, we’re a UCLA student film shoot.” And they said, “Well, do you have permission?” And I said, “Oh sorry. We need permission?” He said, “Oh yeah, you need to call the blah, blah manager and everything.” Well, if they had just looked over there, they would’ve seen Orson Welles sitting in this convertible car, and they didn’t. Don’t do this at home or whatever that warning is, but those were the days when you could do that. The gates were open, so come on. We didn’t break in or anything.

CS: There weren’t 50 people on the set going on Twitter like, “Hangin’ with Orson Welles!”

Marshall: Yeah, yeah, right, exactly.

CS: I remember, and I believe this is in ’85, it was announced that Orson was going to direct an episode of “Amazing Stories” with Burt Reynolds. Is that true?

Marshall: I don’t remember that.

CS: You don’t remember that? Peter vaguely recalled it, but you worked on that show.

Marshall: Yeah, yeah. I’m not saying it didn’t. I don’t remember it, but I know that Orson and Burt got along, so it kind of made sense. I mean, we were trying to get really good directors.

CS: Cameron Crowe was there during the “Other Side” shoot. I was looking all over for him. Is he actually in the final cut?

Marshall: I don’t know. I haven’t looked that closely. There are a couple of people that keep asking me, “Am I in? Am I in?” We all just tried to come up with the people that we remembered that we asked to come and be in it. There’s a lot of shots where we’re like, oh, there’s Neil Canton, you know?

CS: A film you produced that you probably don’t get asked about a lot, but I just love to death, is “Joe Versus the Volcano.”

Marshall: Oh I love that one.

CS: From what I understand, it was a situation where John Patrick Shanley had just won the Oscar for “Moonstruck” and Spielberg just called and was like, “Hey, do you want to do something?” And he was like, “Yeah, I want to do this.” And he was like, “Okay.”

Marshall: Well, yes and no. John was obviously another incredible mind in all different areas, a storyteller, let’s say. I can’t remember… is that the first thing we did with him? I think we knew him before then, or he had written something for us. We just thought that “Moonstruck” was great, and those were the days of Amblin where we called and said, “What do you want to do?” It was Kevin Reynolds or Joe or even Zemeckis, and he said, “I want to make a movie.” We said, “Great. What do you got?” And he said, “Well, I’ve got this kind of crazy idea.” And it was. As we did with first-time filmmakers, we surrounded him with people who were experienced and could help him put his vision up on the screen. And that opening sequence, where he gets fired is one of my favorites.

CS: It’s unbelievable, yeah. It’s an interesting movie because it has one foot in the cinematic and another foot in the theatrical, very proscenium arch. At the time some critics complained that it’s like a play. Now you look at filmmakers like Wes Anderson and it’s that same style.

Marshall: Yeah he was, again, setting his own style and he had a great cinematographer. We were also making “Always” at the same time, and we were all shooting over on the MGM lot and we’d go back and forth. It was a really golden age for Amblin. I’m happy we made it, and then John wrote a bunch of stuff for us after that.

CS: For you specifically, too.

Marshall: Yeah, for me too, yeah.

CS: Do you remember seeing the movie as it came to be, and then having trouble figuring out how to market it and who it was for?

Marshall: Yeah, they sort of had a marketing issue. It was so unique and new that I don’t think they knew what to do with it at Warner Brothers, you know? I’m glad you liked it.

CS: I think you just mentioned Joe, is that Joe Dante?

Marshall: Yeah.

CS: He’s one of my favorites as well, because he’s one of maybe a handful of directors where you can just watch a minute of his movie and be like, “Oh that’s a Joe Dante movie.”

Marshall: Yeah, exactly.

CS: You guys made a lot of pictures together. Can you talk a little bit about working with him?

Marshall: Well, I love working with him. I think one of the things that if I look back, all of the directors I work with have great senses of humor, and he’s no exception. He’s really fun. He’s really funny and he’s a huge movie lover. He’s steeped in the history of movies and in the language of filmmaking. That’s why, when you see his movies, you go, “That’s a Joe,” because he knows the stamp. He knows what he wants. He’s not just going, “let’s get 10 shots. Let me get the coverage here.” He has a point of view, the same as Zemeckis. We had great filmmakers back then that we worked with, and I’m honored to have worked with him. But Joe, in particular, because he has such a quirky sense of humor that he puts in the movies. When you look at “Innerspace” and it’s just like, wow. What a movie.

(Photo Credit: Getty Images)

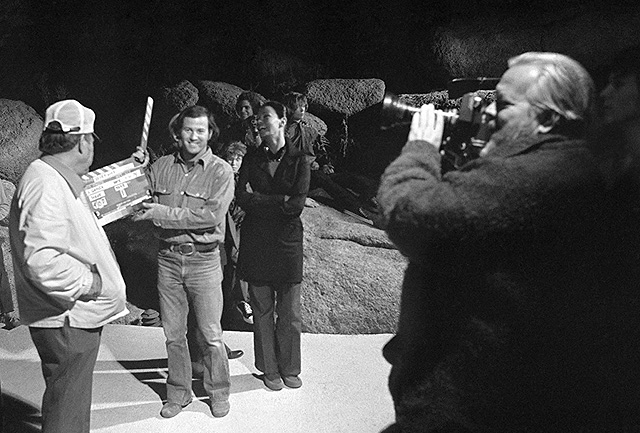

The Other Side of the Wind

-

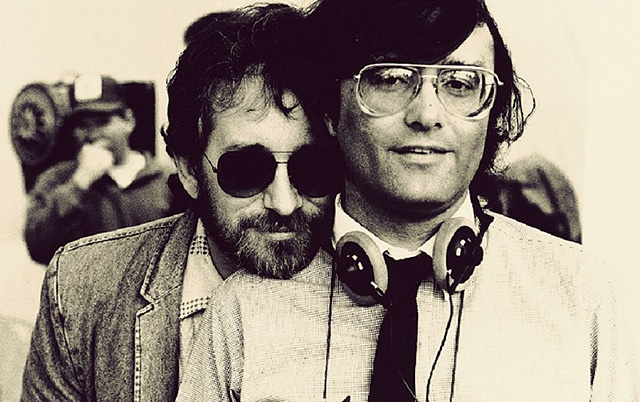

They'll Love Me When I'm Dead

-

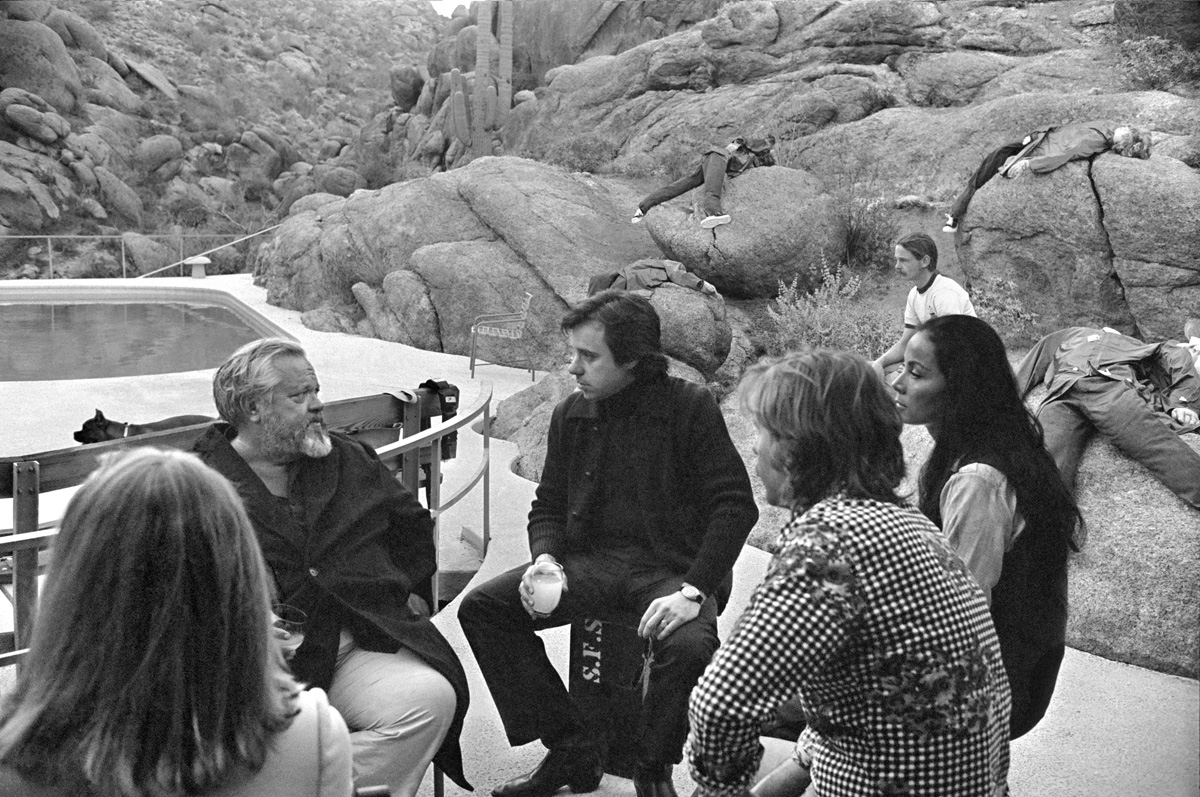

The Other Side of the Wind

-

The Other Side of the Wind

-

The Other Side of the Wind

-

The Other Side of the Wind

-

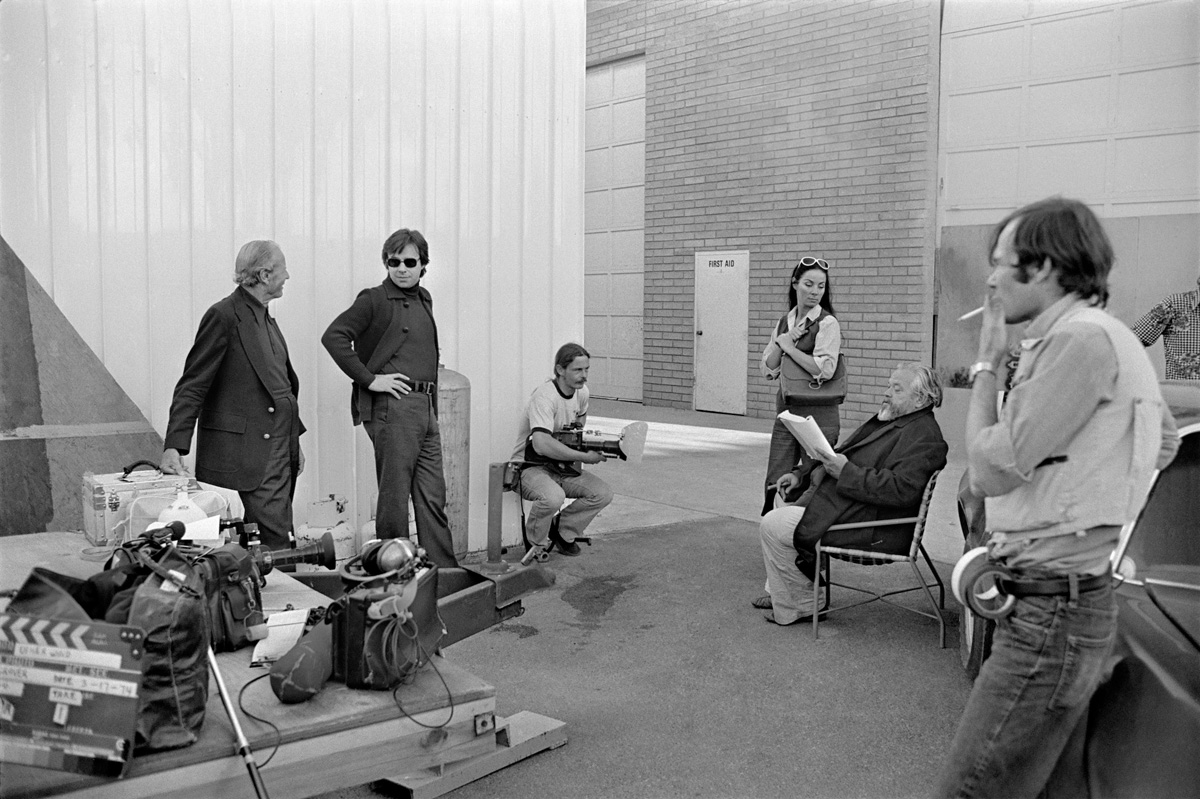

The Other Side Of The Wind

-

The Other Side Of The Wind

-

The Other Side Of The Wind