ComingSoon.net had the opportunity to chat with Emmy nominee John Rhys-Davies (Shogun, The Lord of the Rings films, Indiana Jones franchise) about Grizzly II: Revenge, the horror sequel nearly four decades in the making from director André Szöts. You can check out the interview below and order your copy of the movie here!

RELATED: CS Interview: The Cast of Cobra Kai on Season 3

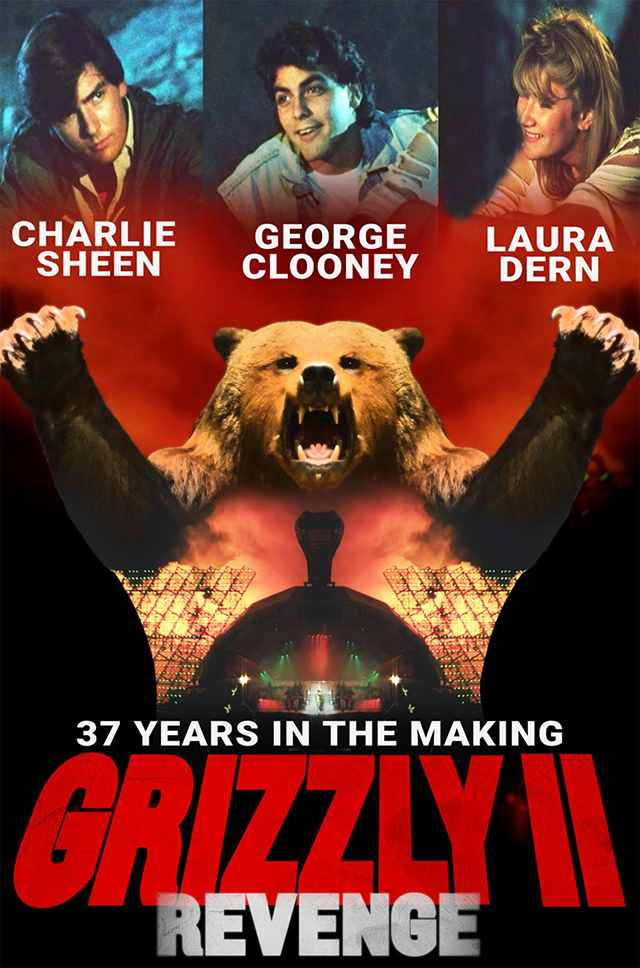

Reacting to the slaughter of her cub, a 15-foot grizzly bear seeks revenge and kills anyone that gets in her way. The terror continues as the giant grizzly finds its way to a major concert to go on a killing spree.

Written by Joan McCall and David Sheldon, the thriller also stars Charlie Sheen, George Clooney, and Laura Dern. The movie is a follow-up to William Girdler’s 1976 Grizzly and is finally hitting select theaters and VOD this year.

RELATED: CS Interview: Roberto Benigni on the New Reimagining of Pinocchio

ComingSoon.net: I’ve actually known about this movie for a long time because in horror movie circles, there aren’t a lot of, A, movies that were never completed or are missing, and two, movies with this many names, including yours. It’s pretty unprecedented. I know a version of this story, but can you talk to your experience of sort of being there on the set, as this train was collapsing on the tracks?

John Rhys-Davies: We had a lovely Hungarian director called André Szöts. It was his big opportunity. He was struggling because the producer didn’t turn up. My correction. The producer turned up for one day and then that’s it. The Hungarian producers were doing their best. This was going to be their entrée into the big-budget world of American filmmaking. This was going to transform the film industry of Hungary, which was constrained and of course, oppressed by being in the Soviet Bloc and itching to be able to get out into the world. Very strong independent streak that had been ruthlessly suppressed, what, 30 years before. The Hungarian uprising, I mean, it’s heartbreaking.

And so, it was important to them, it was important to the country. And they were taking it very seriously. One never really got to know exactly what was happening financially in the background. But as you know, in the end, prison sentences were served. But it was a – one-time, actually, I met him twice. I think I met him in the States as well. A charming, confident, easy man, who, in that freelance producer way – and there were lots of them in those days, you know?

CS: Joe Proctor. And this is the guy who absconded with the funds for the film?

Rhys-Davies: [Laughs] Don’t forget. This is a time when suddenly we had VHS and you could watch a movie over and over again at home. You could own a movie, you know? And there was suddenly more of a demand than the big studios could ever meet and produce. And suddenly, there were funds from video cellars and things like that. There was a lot of money around. There were a lot of people putting money together. There were some notorious – and I’ve got to be very careful, they may still be alive, and they were connected, I believe, is the euphemism.

CS: They were these guys.

Rhys-Davies: Yeah. They could oblige you to have all your trousers shortened to the knee, you know? I had five percent of one of the films that they financed and that vanished, too. [Laughs] It was a little bit like the Wild West. But it gave wonderful opportunities for a lot of young actors. One or two of them did quite well afterwards in this film. And I cannot emphasize how much you actually learn when things go bad. You do a Bond film, and things go wonderfully. You do Lord of the Rings, you learn to appreciate the genius of great producers, who have the foresight and organization, the plan B, the plan C. I remember when we were doing Lord of the Rings, we were meant to be – we were going down to Queenstown to film a five, six-week, maybe two-month section. We got down there and the rain fell. And it fell. The production office is here. The center of the town is there. It is three miles between the two. The rain hits a hillside so much that it wipes 13 houses out and the main road, right.

CS: Wow.

Rhys-Davies: So now it’s a single track, 19-mile journey from the town to the production office. There was suddenly a little bit of commotion, that when I got back from the production office, where I had been told to collect a pair of Wellington boots. I got back and I got into my hotel by step ladder to the first floor because the ground floor was underwater. That was the night the classic daily schedule went out with a note, “There will be no filming tomorrow because the lake is underwater.” Not just the lake, but you know, 30, 40 miles around it flooded. So we did not work that day. We moved the following day to another part of New Zealand. You understand, you got what, 20 principles that you’re moving. You’ve got 200 horses. You’ve got a huge number of extras. You’ve got a crew of roughly around 200. And you’re moving in South Island, New Zealand, where the hotel industry hasn’t developed yet. So you’re really trying to find accommodation that will take three crew members there, two crew members there…

CS: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Rhys-Davies: A logistical nightmare. We did not film on the day that the lake was underwater. We traveled the next day, and we resumed shooting the day after that.

CS: It’s incredible.

Rhys-Davies: When you’ve got production ability like that, you are in the higher realms of filmmaking. But we struggled on. We struggled on. There were some difficulties. I think I do recall that one of our actors, and I shall not mention his name, it was hard to tell which was the greater, his ego problem or his nose problem. The quantifies of powder that he was putting up his nose, plus giving him a certain personality, a quality of aggression and a belligerence perhaps.

CS: This was on Grizzly, just to clarify? This was Grizzly you’re talking about, right?

Rhys-Davies: This is Grizzly yes sir.

CS: Okay I’m like, was that Ian McKellan, was that Elijah Wood? Who was that?

Rhys-Davies: [Laughs] I’ll tell you what, you never saw a lovelier [cast] than Lord of the Rings. There was only one miserable son of a bitch on it, and I wore his boots every day.

CS: But in terms of your time in Hungary on the set, did everything collapse mid-shoot, towards the end of the shoot? At what point in the shoot did everything kind of fall apart?

Rhys-Davies: Well, as Claudius will say, I am rank corruption mining all within, infects unseen. You know, on the surface, it looked okay. There were suddenly a few urgent sort of production meetings and things like that, but we continued shooting. We were looking forward to the grizzly bear.

CS: Because they built like a big animatronic creature, right?

Rhys-Davies: That’s right. And it didn’t work. Now I’ve heard different reasons why it didn’t work. The from the top thing was the guys couldn’t do it, they couldn’t deliver the thing. If we had some money, we might have development money to be able to do this thing.

CS: Right.

Rhys-Davies: So I can only pass on gossip as far as that is concerned. But really, we managed to shoot the big rock festival and because we did not have a proper animatronic bear, we had a lot of issues there. And I think it was after that, and that was quite later on in the shooting, that things really did fall apart because my sense was that people weren’t being paid. So some of us had managers and agents who made sure we got paid sort of upfront. I don’t think any overage was ever paid, but I can’t remember now. It’s 38 years ago or something like that.

CS: Right. But there were probably like, a lot of below the line people that didn’t get – yeah.

Rhys-Davies: Almost certainly, that was true. But you understand the madness being in Hungary at that time, it was Soviet. You know, it was well known that in the rather lovely, stately hotel room that we were staying in, and I can’t remember, it’s one of the great hotels in Hungary, an old palace overlooking the river. And there were mirrors in every room that you could not get out of the view of. I did call my wife once. I put the phone down and I thought, oh I forgot to tell her. And called back and I heard the last three or four phrases of the call that I’d had before.

CS: Yeah, you gotta be careful they don’t get any kompromat on you.

Rhys-Davies: Absolutely. Well, I think the policy was to do whatever you were doing very publicly facing the mirror with a big of that, you know? Which seemed to be the favorite sort of response.

CS: But do you have any memories – like you had a very interesting accent. You got to get basically crucified. Your character gets to do a lot of cool stuff. Do you remember the actual experience of shooting?

Rhys-Davies: I do. And I loved it. I mean, it’s a super part. There was going to be more to it, but somehow, we never quite got around to shooting that. But Bouchard, you know actors can very rarely judge their performances. And you’re either immersed in the part or you’re judging it and performing at the same time. And it was 1985, was it ’84 or something like that?

CS: I think it’s ’83.

Rhys-Davies: ’83? Good god. Well, you know, I was what? 14 years out of drama school. I was in my early, mid-30’s. I was beginning to make a little bit of a dent in the recognition thing.

CS: Yeah, because this was post Raiders.

Rhys-Davies: Post-Raiders, post-Shogun. And post-Victor Victoria. But I thought of it as being actually one of my better performances at the time. Now since I haven’t seen it, I’d be interested to do it. I mean, I probably will go, oh my god, how could I have imagined? But at the time, I thought, actually, I think that this is an interesting character and I played him interestingly. And so, I was a little bit disappointed when it didn’t sort of work out. But you know, I consoled myself with at nighttime, taking $100 in American cash down under the bridge and meeting the guy who was connected and buying an eight-ounce tin of caviar for $100.

CS: Whoa.

Rhys-Davies: Oh yes, yes, yes. I was nearly put in prison and never emerged if they sort of caught us in those days, but the smuggling was well known, and that one really, they weren’t worried about.

CS: I wouldn’t think so.

Rhys-Davies: But Hungary at that time was a fascinating place. The Hungarians are also one of the cleverest people on the planet, you know? Basically because they all speak about five languages. And I loved that part of it. The Hungarian production team I thought were super people. You know, when you’re young, a young up and coming actor, you don’t really pay much attention to the young kids who are playing the small parts. And you know, you just say hi, hello and I’m off now to go learn my lines and this sort of thing. You see, it’s only when you get older, I suppose, and not that the ego ever vanishes, but I suppose you feel confident enough and interested enough to actually look around and see what other people are doing and what they’re like. And but that’s happened after. So I cannot give you any great stories about George Clooney.

CS: Yeah, sure.

Rhys-Davies: Or Laura Dern. Or a young Sheen. I remember meeting Sheen and thinking, yeah, interesting kid. His father’s a good actor.

CS: Well, they all had a big of lineage, didn’t they?

Rhys-Davies: They did.

CS: Yeah.

Rhys-Davies: Yeah, they did, which is presumably how the career gets its start. But your destiny in the end, you can’t get by on dad indefinitely. In the end, you make your own destiny and they made their own destiny.

CS: Yeah, more or less.

Rhys-Davies: You know, I very rarely criticize my fellow actors. It’s such a mad business. And anyone who achieves their 15 minutes of fame actually has something. One tends to respect those whose careers have long legs, you know, they are the warriors that have survived. They have [enemies] and the enemy’s promise, drink, drugs, illness, whether brought on foolishly or just inadvertently, like coronavirus.

CS: Right.

Rhys-Davies: In the end, one sort of loves your fellow survivors. But I do now watch the goings on of younger actors and the ones who only got a couple of lines on the set, and I do try and talk to them and pass on the great, wicked stories, which is part of the inheritance of being a victim. We love to bitch and gossip, not in an adverse way, but to tell the great, notorious stories that have kept the profession alive, and particularly theater in the stories, how legendary.